Rebuilding Jerusalem: Nehemiah, Ezra, and the Restoration of Faith

Building the Jerusalem Wall

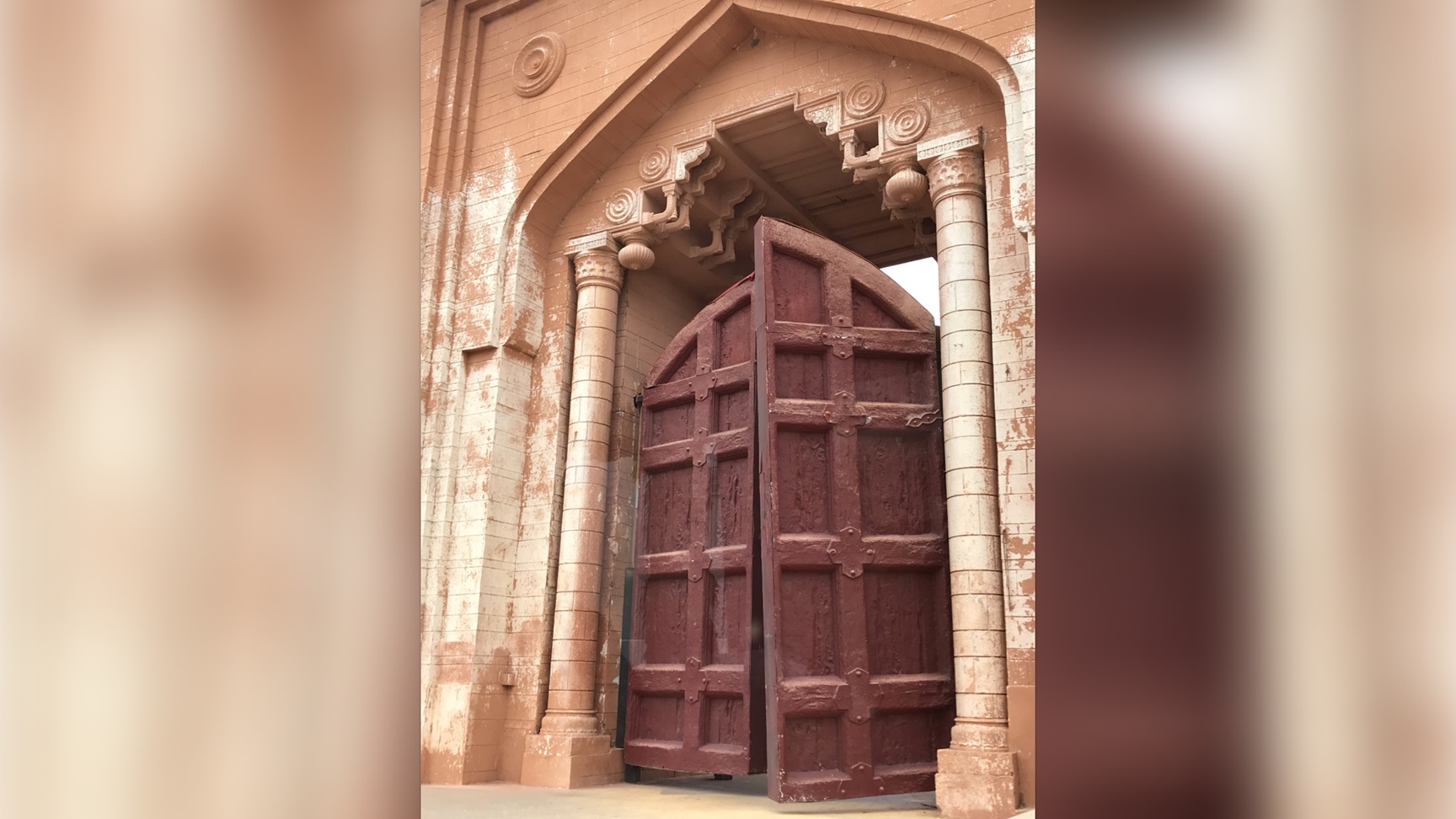

In 444 B.C., Nehemiah, serving as the king’s appointed governor of Jerusalem, made a bold request. He sought permission to cross the river, procure timber for the gates and walls, and rebuild Jerusalem’s defenses. The king granted his request, and Nehemiah journeyed to the devastated city.

Upon arriving in Jerusalem, Nehemiah spent three days surveying the ruins. He secretly toured the city by night and, once acquainted with the full extent of the damage, summoned the leading citizens. As the new governor, Nehemiah wielded considerable power, and the city’s leaders were compelled to cooperate with him. However, Nehemiah faced mockery from Sanballat, the governor of Samaria, who scorned the Jews’ efforts to rebuild the walls, dismissing their task as futile. “Do they think they can rebuild the walls of Jerusalem out of rubbish and ruins?” he jeered.

Nevertheless, Nehemiah remained determined and organized the reconstruction with military precision. Each section of the wall was planned for specific families, such as the priests rebuilding the Sheep Gate and an influential family taking responsibility for the Fish Gate. As the work progressed, Sanballat and his allies grew increasingly hostile, fearing the loss of their influence over the region. They attempted to sabotage the project, hoping to destroy the wall while the mortar was still soft. In response, Nehemiah encouraged the workers to “fight for your homes, wives, and children,” distributing swords to the laborers and organizing defenses. Some men carried their swords while others took on supporting roles, such as blowing the bugle to rally the workers. Against all odds, the wall was completed in just fifty-two days.

The rebuilding of the Temple was only one part of Nehemiah’s mission. Life in Jerusalem had been harsh for the returned exiles. Many had incurred debts they could not repay, resulting in the sale of their own family members into slavery. Nehemiah took immediate action, abolishing the practice of money lending. He also tackled the issue of Sabbath observance, which had been neglected. Merchants sold goods on the Sabbath, and no one had paid the Temple taxes. The Levites, who were supposed to dedicate their lives to Temple service, had been forced into other forms of labor to survive. To address this, Nehemiah ordered the city gates to be closed at dusk on Friday and reopened only at dawn on Sunday. This action effectively blocked traders and merchants, ensuring that the Sabbath would be respected. He also instructed the Levites to return to their Temple duties and oversee the collection of Temple taxes.

Sanballat: The Persistent Enemy

Sanballat, the governor of Samaria, was a staunch opponent of the Jewish rebuilding efforts. He had once been an ally of the Jews but turned hostile when the exiles began to reclaim their homeland. His daughter had married into the family of the High Priest, but after Nehemiah’s arrival, he demanded the end of such mixed marriages. In retaliation, Sanballat sought to disrupt Nehemiah’s plans, even attempting to assassinate him. When that failed, he resorted to fear tactics, hoping to intimidate the governor and halt the work.

After the failure of his schemes, Sanballat sought to build a competing temple on Mount Gerizim for worship, further dividing the Jews and Samaritans.

The Jewish Dispersion and the Samaritans

The Jewish Dispersion, or diaspora, refers to the scattering of Jews beyond Judah after their exile in Babylon. The remaining Jews in Judah were impoverished and often isolated, making them vulnerable to exploitation by neighboring provinces. As a result, many Jews left Judah voluntarily, seeking refuge in Egypt or along the northern Mediterranean coast.

The Samaritans, who had intermarried with Gentiles after the northern kingdom of Israel fell to the Assyrians in 721 B.C., were a mixed race of Jews and non-Jews. When the Jewish exiles returned, the Samaritans initially offered assistance, but the returning Jews rejected their help, deepening the animosity between the two groups. This longstanding rivalry persisted throughout the centuries.

Ezra and the Challenge of Mixed Marriages

While Nehemiah was an excellent organizer and leader, he was less equipped to address the religious and social issues plaguing Jerusalem. Ezra, a scribe from Babylon, took on this role. He was granted authority by King Artaxerxes to appoint magistrates and judges in Jerusalem, ensuring the adherence to Jewish law. Ezra also brought with him valuable gifts of gold and silver for the Temple, which had been taken by Nebuchadnezzar during the destruction of the First Temple.

Upon his arrival, Ezra learned of a troubling issue—many Jewish men had married foreign women, leading to concerns that these mixed marriages threatened the survival of the Jewish faith and identity. According to Jewish religious law, a child was considered Jewish only if the mother was Jewish. The older generation feared that intermarriage would dilute the Jewish identity, creating a future generation that did not speak the Jewish language or follow the faith.

Ezra was deeply distressed by this news and spent the evening in grief before the Temple. He attributed the hardship faced by the exiles to their disobedience to God. The people, acknowledging their wrongdoing, appealed to Ezra for guidance on how to address the issue. Ezra called for a public assembly of all the returned exiles, warning that anyone who did not attend would be excommunicated and have their property confiscated. Despite the cold and rainy December weather, the assembly took place, and Ezra urged the people to confess their sins and divorce their foreign wives.

The process of dissolving these marriages took three months, from January to March, as the court systematically annulled the marriages between Jewish men and their non-Jewish wives. This caused great hardship for the women, many of whom were left with children and forced to return to their parents’ homes. This divisive measure further alienated the local people, particularly the Samaritans, deepening the rift between Jews and their neighbors.

The Story of Ruth: A Counterpoint to Ezra’s Measures

Not everyone agreed with Ezra’s harsh measures. Some saw the story of Ruth, the great-grandmother of King David, as a powerful counterpoint to Ezra’s policies. Ruth, a Gentile woman, married Boaz, a Jew, and from their union came a lineage that led to King David. If God could bless such a union with such a noble outcome, what right did Ezra have to force Jewish men to divorce their foreign wives? The story of Ruth serves as a reminder that the purity of the Jewish race was not defined by ethnicity alone but by faith and God’s providence.

In conclusion, the rebuilding of Jerusalem was not only a physical endeavor but a spiritual one as well. Nehemiah’s leadership restored the city’s walls, while Ezra’s reforms aimed to restore the faith of the people. Yet, the challenge of maintaining Jewish identity in a world of mixed cultures and traditions remained a contentious issue, exemplified by the tension between Ezra’s strict measures and the more inclusive message of the Book of Ruth.