Return from Exile and Life under the Persians: A New Beginning

Life Under the Persians

Under Persian rule, agriculture, industry, and trade flourished, and the construction of vast roads improved communication across the empire. Darius I, the third ruler of the Persian Empire, was undoubtedly one of the greatest administrators the world has ever known.

The Persians were known for both their love of peace and their prowess as fighters and cavalrymen. The empire was divided into twenty satrapies (provinces), each governed by three key officials: the governor, responsible for civil governance; the commander, in charge of the military; and the secretary, who maintained communication with the royal court in Susa via fast-moving couriers and well-trained horsemen. This system ensured that no single official could rise to challenge the king, as each ruler was constantly watched by the others to prevent rebellion.

In addition to their military and administrative skills, the Persians were deeply religious people. Their founder, Zoroaster, who lived around 1000 BC—approximately the same time as King David—taught the worship of Ahura Mazda, the god of light, purity, and truth. The Persians were open to adopting the religions of other peoples, especially if it helped maintain peace. For example, Cyrus the Great was crowned in Babylon by the priests of Marduk and, similarly, allowed captive peoples to retain their own laws, languages, and customs. Most notably, Cyrus encouraged exiled populations to return to their homelands.

Return from Exile

The Persian approach to conquered peoples was not oppressive. Despite his reputation as a stern ruler, Cyrus was remarkably humane and liberal. He treated captives with respect and encouraged them to continue worshipping their own gods. His famous decree, allowing exiled peoples in the Babylonian Empire to return to their ancestral lands, included the Jews. Not only did Cyrus grant the Jews permission to return to Palestine, but he also ordered the return of the sacred temple treasures that had been plundered when Jerusalem fell to Nebuchadnezzar.

Why was Cyrus so generous? Some scholars suggest his Zoroastrian beliefs influenced his policy, as the religion promoted virtues like goodness and truth. Others note that Isaiah had prophesied this return long before Cyrus issued his decree, even during the reign of Hezekiah.

Cyrus’ decree permitting the Jewish exiles to return to Jerusalem was issued in 537 BC. However, not all Jews were eager to return. Many had established families, businesses, and fortunes in Babylon. The fertile land of Babylon held more appeal than the barren hills of Judah. For younger generations, returning home seemed an adventure; for older ones, it was a final opportunity to be buried in the city of their ancestors.

Those who did return were pioneers, carrying with them dreams of the city and temple their ancestors had once cherished. Yet, upon their arrival, they were met with the stark reality of desolation. The once-great city of Jerusalem lay in ruins. A first group of exiles returned in 536 BC, followed by a larger group in 570 BC.

The Cyrus Cylinder, now housed in the British Museum, records his policy:

“All kings of the entire world from the Upper to the Lower Sea brought their heavy tribute and kissed my feet in Babylon. I returned to the sacred cities across the Tigris, which had been in ruins for a long time, and I restored their sanctuaries. I also gathered all their former inhabitants and returned them to their habitations… May all the gods I have resettled in their sacred cities ask daily Bel and Nebo for a long life for me.”

It is clear that Cyrus’ decree not only benefitted the Jewish exiles but also other peoples, restoring their temples and returning them to their lands.

The book of Ezra offers a similar account through the eyes of the Jewish people:

“Thus saith Cyrus, King of Persia: The Lord God of Heaven hath given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and He hath charged me to build Him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Who is there among you of all His people? His God be with him, and let him go up to Jerusalem and build the house of the Lord God of Israel… And whoever remains in any place… let him help with silver and gold and with goods and beasts. And Cyrus the king brought forth the vessels of the house of the Lord, which Nebuchadnezzar had brought forth out of Jerusalem…” (Ezra 1:2-8).

Thus, the Jewish exile in Babylon came to an end.

The Homecoming (Ezra 1, 3, 4; Haggai 1:2-11)

It is important to note that Judah had not been completely depopulated during the exile. Not all Jews had been taken to Babylon. Some had fled into the hills, while others had settled in Egypt, where they even built a temple, violating Jewish law. Over the years, Palestine had absorbed exiles from other conquered lands, and these newcomers integrated their own religions and customs into Judaism. The Jews returning from Babylon viewed these people as foreigners and were reluctant to associate with them.

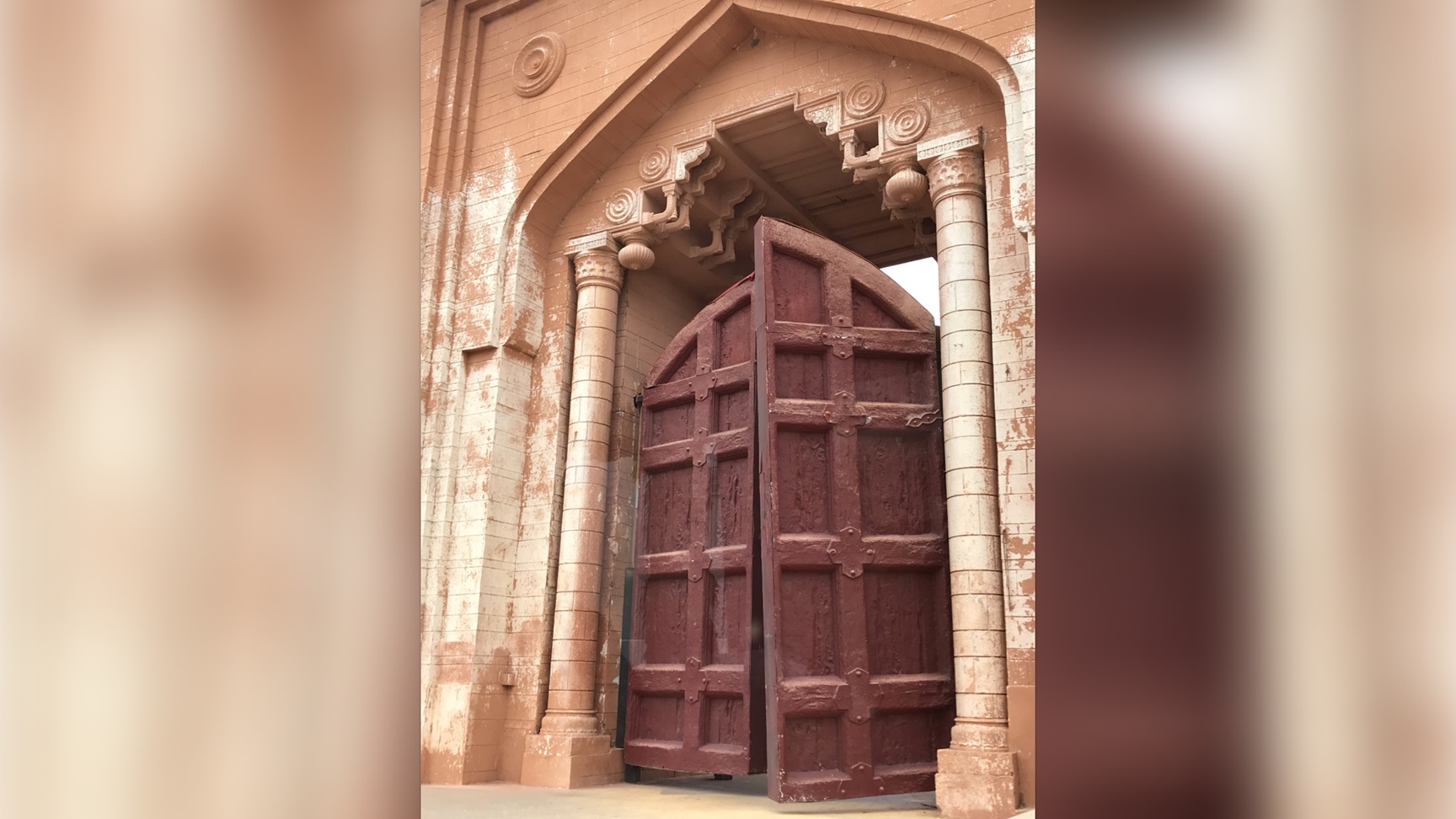

Thus, the land to which the exiles returned was not the one they had dreamed of. The journey had been long and perilous. They endured extreme heat, cold, hunger, thirst, sickness, and fatigue. Upon their arrival in Jerusalem, the sight that greeted them shattered their spirits. The city was in ruins. Yet, the exiles settled around Jerusalem, cleared land, and began planting crops.

Seven months after their arrival, the altar of the Temple was rebuilt, and the foundation for a new Temple was laid. However, the Temple was not completed until 516 BC, twenty years later. This delay was partly due to the opposition from neighboring peoples. The “Samaritans,” or “half-Jews,” who had remained in the land, sought to assist with the rebuilding of the Temple, but the returning exiles refused their help. This rejection sowed deep animosity, and generations later, when Jesus walked the land, the hostility between Jews and Samaritans was still apparent.

The second group of exiles arrived in 520 BC, and the rebuilding of the Temple began in earnest. However, the work was delayed when the local satrap, Tattenai, questioned the Jews’ authority to rebuild the Temple. In response, the Jews stated that they had received permission from Cyrus. Tattenai wrote to Darius for confirmation, and Darius sent a letter affirming that the Jews had royal approval. With this confirmation, work continued, and the Temple was completed in 516 BC, just four years after construction resumed. The people celebrated with a seven-day festival, singing songs of joy, some of which can be found in Psalms 149 and 150.

The Rebuilding of the Walls of Jerusalem (Nehemiah 1 & 2)

In the Persian capital of Susa, Artaxerxes I ruled, and his cup-bearer was a young Jewish man named Nehemiah. Nehemiah received troubling news from Jerusalem: the people were in great distress, and the city walls had been broken down. Saddened by this report, Nehemiah prayed to God and, taking courage, approached the king.

The king noticed Nehemiah’s sadness and asked him the cause. Nehemiah replied, “If it pleases the king, and if your servant has found favor in your sight, I ask that you send me to Jerusalem to rebuild the city walls.”

The king granted his request, and Nehemiah set out for Jerusalem, determined to restore the city and its defenses.